Alphabets give their creators scope to celebrate current technology. Cousin Chatterbox's Railway Alphabet (7.1.5) takes pride in all the conveniences of this mode of travel. The Big Ship Great Eastern Alphabet (10.1.7) has "H for Hawse-holes, through which the chain-cables pass... O for Ordnance, fired in cases of need" (with a little girl and a dog huddled up to the big gun) and "X for explosion which burst the great funnel by force."

The Alphabet of Trades (7.1.5) has an interesting mix of old and new: An "engineer is E planning steam machinery" & "Y begins yeoman who is born to plough the land and till the corn." All sorts of things filter into alphabet books. In the Alphabet of English Things (11.1.3),

Z are the zones, that encircle the earth;

When the zero we reach, of all heat there is dearth.

I guess this means Greenwich (?!). In another Alphabet of Trades (11.5.5), c.1865,

N is a newsboy, who plies well his calling,

And 'Latest Edition' always is bawling.

Z stands for zoologist, also for zany;

so please take your choice: that's if you have any.

The picture shows an egghead peering at a lion in a vitrine against a dense black background. The Alphabet of Flowers (11.5.6) has "Oleander, the gardener's pride; He thinks it the finest in all England" grown in a pot like a spindly poinsettia, a sorry pass for the freeway immortal. V stands for Vagrant, Victuals and Virgin in Read's Pictorial Alphabet (10.1.1).

Q was a Quaker, very plain in his dress,

And rather austere, but good none the less.

He carries himself with his thin nose in the air in Tom Thumb's Alphabet (11.5.6) and is pestered by a smirking ragamuffin.

When war creeps into the alphabet books, V shows a veteran uncle with no eye or leg. In The Soldier's Alphabet (13.2.4)

Y is a yokel with funds getting low;

He thinks, as he reads, to the wars he will go

as he stands in the street staring at an enlistment poster.

The Union ABC (2.1.4), dating from the Civil War, shows Lincoln's portrait surrounded by the instruments of destruction. X is a particular challenge to the writers of ABCs. From "X is the next letter" in The Poetic Gift (1.4.12), 1842, it only gets better. Xebec and Xerxes ("An uncle has said I'll tell you about him but now go to bed," in Arthur's Alphabet, 4.4.3) have a long run. Then, xacca and xacotoo (for cockatoo) make an appearance after the existence of Australia registers in England.

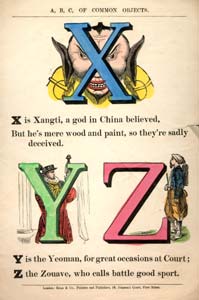

XYZ page from "Read's

XYZ page from "Read's

ABC of Common Objects"

X is Xangti, a god in China believed,

But he's mere wood and paint, so they're sadly deceived.

in Read's ABC of Common Objects (10.1.7).

X stands for excellent, when on barrels of beer;

So the more x's, the better the cheer.

from Routledge's Picture Gift Book (11.5.5). Lastly, there is the bang-up "Xeter Xlex Xtolled an Xcellent Xpert" in Peter Piper's Painting Book (16.2.3).