This week, while libraries around the United States are celebrating Banned Books Week, San Francisco Public Library wanted to shine a light on young people who fought for the right to read, learn, and express themselves, even when conditions were difficult. We salute these young warriors for intellectual freedom!

Each day from September 22 – 28, we will share a story and photo, highlighting a young person who fought for the right to read. Look for our display at the Main Children's Center, and read their stories below! #FreeToReadFreeToBe

Read About

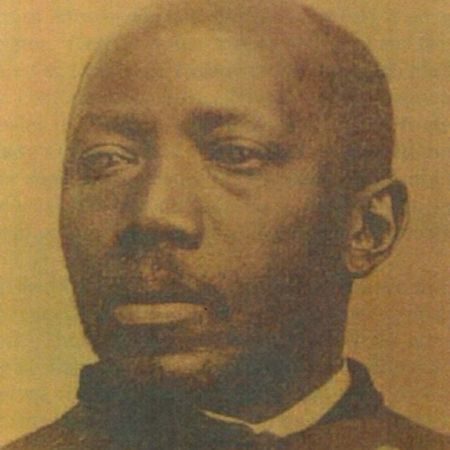

George Moses Horton, 1798?-ca.1880

George Moses Horton loved words, ever since he was a little boy. But because he was a slave in North Carolina in the early 1800s, no one cared if he learned to read or write. In those days, slaves were considered the property of whomever owned them. Slaves could be sold or traded away, like we today would sell or trade a car or a toy or a computer game.

Few white people in those days believed that an African American slave was capable of learning to read and write well. They certainly did not believe that a young African American slave could become a poet who wrote beautiful lines that moved people’s hearts.

But that is exactly what George Moses Horton did.

When he was only seven or eight years old and already carrying heavy loads on his master’s property, he would try to stop and listen whenever he heard the white children learning their ABC’s. George’s mother would have loved to have taught her son to read, but she herself had never been allowed to learn.

George took every opportunity he got to study by himself. After he had learned the alphabet only by listening to the other children, he found a worn-out old spelling book. Late at night, during the few hours allowed to him for sleeping, he would stay up late, his eyes burned by the smoke from the firelight, and teach himself to read.

His mother had given him her own precious hymnal, filled with beautiful and inspiring songs. Whenever he could, he read from the Bible, from newspapers, and even advertisements.

Words sang in George’s head. He hadn’t yet learned to write, so he carefully memorized the poems he composed. He said his poems to himself as he worked from morning to night tending cattle. His words helped him to stay strong. They helped him become a confident young man who knew he had something important to say.

George was separated from his family when he was 17 and given to his master’s son. He worked in the fields on his new master’s property, but on Sundays, he walked eight miles to Chapel Hill, to sell fruit and vegetables to the students and faculty at the University of North Carolina.

Some of the white students made fun of George. But many were won over by his gracious manners and his gift for words. So much so, that he was soon composing love poems that he sold for 25 cents each to the young students to give to their sweethearts. The wife of one of the professors befriended George and taught him to write down his verses. He devoured the books his friends gave him: Shakespeare, Lord Byron, the ancient poet Homer.

Despite remaining his master’s property, George was able to earn his own money, dress well, and make friends among educated people. This was a very rare experience for an enslaved person at the time. His friends helped him publish his work in newspapers and, finally, in real books. George saw his name on the covers, and knew he had become an author.

George wrote poems of love, friendship, humor, happiness, and grief. He also wrote about the injustices of slavery, becoming the first African American slave poet to do so. People all over the country who were working to end slavery were inspired by his words.

When George Moses Horton was a man in his 60s, the Union victory in the Civil War ended slavery. He lived the last 18 years of his life as a free man.

Anne Frank, 1929-1945

Young Anne Frank had always dreamed of becoming a writer. When Miep Gies, a family friend, gave her a diary for her 12th birthday, she started writing about her experiences, her ideas, and her private thoughts. Soon after receiving this gift, Anne’s father announced to the family that they had to go into hiding.

During Anne’s life, persecution of Jewish people in Europe had been growing more and more intense. Anne’s family had already fled from Germany in 1939. As Jews, they had been stripped of their citizenship. When Anne arrived in Amsterdam as a four year old, she was already stateless. Amsterdam provided some respite from the Nazis. Anne’s father, Otto, started a business and hired employees. He was able to make a modest living for his family. Anne and her sister Margot attended school, though after the Nazis invaded the Netherlands, Jewish children had to attend separate schools. They also had to wear yellow stars to identify themselves as Jews. Otto Frank had already made a plan to go into hiding with his family, but when the older sister, Margot, received a notice to report to a work camp, they decided to go immediately. With the help of a small group of friends and co-workers, the Frank family hid in a rear house they called “the Annex.”

For two years, Anne continued to write in her diary, documenting life spent in hiding. Life in hiding was difficult. All the occupants of the Annex had to remain quiet during the day. Anne and the other residents read books, sewed, or quietly prepared food while workers were in the warehouse below. They all tried to keep up with the events outside by listening to radio broadcasts and reading the news. The helpers brought food, and any information they could to the Annex. The windows were covered, and they could never go outside. Tensions were high and the residents argued with each other. In 1944, Anne wrote, “I can shake off everything if I write; my sorrows disappear, my courage is reborn. But, and that is the great question, will I ever be able to write anything great, will I ever become a journalist or a writer?”

During the summer of 1944, someone tipped off the Nazis about the Annex. Nazis arrested Anne, her family, and the others who were hiding with them. Unable to take anything with them, the diary remained in their secret annex, and one of the helpers, Miep Gies took the diary and hid it from the Nazis. After the war, only Anne Frank’s father returned to their hiding place. Everyone else had died in the camps. Anne’s diary, published by her father, is a rare account of a young teen’s life suspended during war time.

Without school, entertainment, and participation in life, the diary reveals what it was like to be in hiding – the constant fear and vigilance, and tiny acts of humanity.

The enduring popularity of the diary speaks volumes about the hopes and dreams of young people, caught in a situation beyond their control. Anne’s optimism and hopeful tone is both poignant and inspiring. War silenced this young voice far too soon. Her diary survived as a record of the era, but also as a universal plea for humanity. Mr. Frank made Anne’s dream a reality, but one cannot help but wonder what more Anne would have written, had her life not been brutally cut short.

Otto Frank published Anne’s diary in 1947. It has since been translated into 70 languages. The Annex was turned into a museum in 1960. In 1972 Miep Gies and her husband Henk were awarded the Yad Vashem Medal of Honor for their bravery in helping Jews during World War II, and in 1994, Miep won the Wallenberg Medal as an outstanding humanitarian. Since its publication, Anne Frank’s diary has sold more than 30 million copies, and The Annex has hosted more than 1.2 million visitors every year. Anne did achieve her dream, and her story survives.

Sylvia Mendez, b. 1936

Sylvia walked to her locker on her first day at a new school. She was nervous, and the other children stared at her. One boy shouted, “You don’t belong here!” But Sylvia didn’t give up. Encouraged by her parents, she and her siblings returned the next day, and the next. The year was 1947, seven years before the Supreme Court of the United States handed down its decision to desegregate public schools in Brown v. Board of Education. What was happening?

In a little-known court case in California, the Mendez family argued that their children had the right to attend their local public school, and they should not be forced to attend the “Mexican School,” which was farther away from home, was poorly maintained, and did not have the resources that the regular elementary school had. The lawsuit, Mendez vs. Westminster School District, was the first in the nation to ensure that all children had the right to attend the same public school.

When Sylvia Mendez was eight years old, her family moved to Westminster, California. Soon after, her aunt took Sylvia, her brothers, and her cousins to the local elementary school to enroll. The school refused to enroll Sylvia’s family, and instead told them they had to attend the school for Mexican students. Sylvia’s parents were furious. They joined together with other Mexican American families who were also denied the opportunity to enroll their children and sued the school district. In 1946, they won. The School District appealed, but the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals in San Francisco upheld the decision. Sylvia and all the other Mexican American children were allowed to attend the same schools as the white children. Mendez v. Westminster Board of Education led the way as the rest of the country grappled with school segregation.

Sylvia Mendez, age 10

In addition to the court battle waged by the Mendez family and the other plaintiffs, two notable figures played a role in this court case. Thurgood Marshall, then president of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), submitted amicus briefs to the court in California, affirming their support for the cause. He later went on to represent the plaintiffs in Brown v. Board of Education. After the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals in California decided in favor of the Mendez family, the governor of California, Earl Warren, signed a law ending segregation of school children in the State of California. Seven years later, as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, he would preside over Brown v. Board of Education, the decision that ended school segregation in the United States.

Being the first Mexican American children to attend a white school wasn’t easy for Sylvia and her brothers. The white students shouted insults at them and told them they didn’t belong, but Sylvia held her head high, and soon she made friends. She finished school and went on to attend college. As an adult, Sylvia made sure people remembered what her parents had done. Plenty of people know about the Brown decision, but the Mendez case isn’t even taught as part of the K-12 curriculum in California. Sylvia Mendez proudly states that “California was number one,” with school desegregation. She travels and speaks about her family’s role in Mendez vs. Westminster School District. In 2011, President Obama awarded Ms. Mendez the Presidential Medal of Freedom, which is the highest civilian award in the U.S.

Sylvia Mendez receiving her Presidential Medal of Freedom, 2011

Peter Sís, b. 1949

When Peter Sís was growing up in Communist Czechoslovakia in the 1960s and ‘70s, a lot of things were banned: rock music, blue jeans, long hair, radio programs from the United States and Western Europe, and plenty of books that he would have liked to read.

The government, under the control of what was then the Soviet Union, forced people to participate in parades and mass sporting events that glorified the Communist way of life. Children had to join the Young Pioneers, the government-sponsored youth organization, and wear its symbolic red scarf.

As a boy, Peter loved to draw pictures. At home, he drew whatever he wanted. But at school, the authorities told him what he could and could not draw.

In those days, kids were asked to “inform” on their parents, to tell on their parents if they said anything against the government. Government censors routinely opened people’s mail. Many people in Communist Czechoslovakia who said or did something the authorities did not like were sent to prison, forced to leave the country, or even executed. Writers, artists, and musicians were forbidden to publish or perform, and many who stayed had to earn their livings doing hard manual labor. Many were sent to prison camps to do dangerous work mining uranium.

For many people, the easiest thing to do was to keep their opinions to themselves.

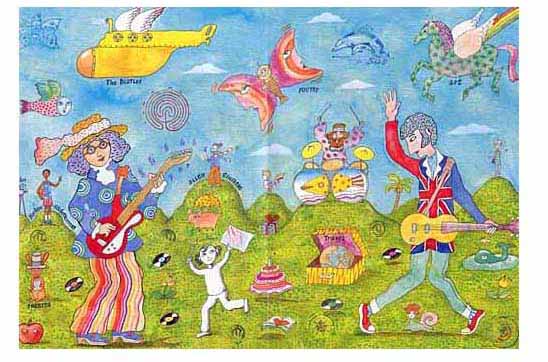

But Peter’s imagination soared beyond the narrow space where others wanted to confine it. As he grew into his teens, he listened to forbidden music, like the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, that people managed to smuggle into the country. He began to question what he had always been taught to believe.

Peter and his friends started their own rock band. He painted brilliantly colorful pictures to show how music made him feel. Because it was impossible to get them behind the “Iron Curtain” that shut off Czechoslovakia and the rest of the Communist bloc from the West, he and his friends made their own stylish clothes, guitars, sunglasses, and even shoes!

In 1968, during the Prague Spring, Czechoslovakia experienced a few brief months of greater freedom. Censorship was lifted, and people’s hearts were lifted, too. Writers, artists, and musicians produced a flood of new creative work. But on August 21, tanks and soldiers from the Soviet Union and other Communist countries invaded, and a long, gray period of repression, censorship, and fear began again.

Peter still dreamed of the freedom to enjoy and create the music, art, books, and animated films he wanted to. He painted dreams and maps of imagined worlds, but he also painted nightmares. Only in his imagination could he take flight, on a bicycle with wings, into the world he wanted to see.

In 1989, the Velvet Revolution transformed Czechoslovakia into a free country. Today, the Czech Republic is a lively, prosperous democracy, and people can draw, sing, read, and write whatever they want. “Sometimes,” Peter wrote about this new freedom, “dreams come true.”

Peter Sís immigrated to the United States in 1984, and now lives in New York. In 2003, he became the first children’s book illustrator to win the prestigious MacArthur “Genius Grant” Fellowship. Three of his books - including his illustrated autobiography The Wall: Growing up Behind the Iron Curtain - have received Caldecott Honor awards from the American Library Association.

If you will be visiting Prague, Czech Republic, from now until January 20, 2020, you can see a large exhibit of Peter Sís’ work, called “On Flying and Other Dreams,” at the DOX Centre for Contemporary Art. The artist himself personally helped to transform the exhibit space into his own land of dreams.

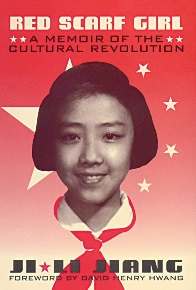

Ji-li Jiang, b. 1954

When Ji-Li Jiang was 12 years old, she had everything: popularity, good grades, athletic ability, and a sunny apartment in Shanghai where she talked to her family and played with her cat. She had a bright future in the China of 1966. One day, Ji-Li got an invitation to audition for a dance program at the Central Liberation Army Arts Academy. If she got accepted she would tour the country to tell everyone in China about the wonderful new world the government of Chairman Mao Zedong was creating.

But her family could not let her audition. Even if she passed, they knew she would not be allowed to join. Because even though she proudly wore the red scarf that symbolized China’s revolution, Ji-Li’s family was part of the educated middle class. That made them politically undesirable in the new China. From 1966 to 1976, the Cultural Revolution tried to destroy all influences the government disapproved of: books, art, music, higher education, even certain styles of clothing and certain words. Having private thoughts that went against government policy was unacceptable.

Ji-Li had always loved reading, especially fairy tales. Every Sunday, she sat in a friendly bookseller’s stall and read dozens of them, and she loved reading the patriotic stories in her school library. But things were changing. On her last day of school before summer vacation, she looked into the library and saw half the shelves empty. A sign said, “Closed for Sorting During Summer Vacation.” Ji-Li later wrote, “I knew that many of my favorite books...would be sorted away forever, declared poison under the new standards.”

One night, when Ji-Li was asleep in bed, young Red Guards soldiers stormed into her family’s home to search for forbidden items. They tore open the family’s cupboards, drawers, and closets, and spilled all their possessions into the floor. Ji-Li’s beloved stamp album, filled with colorful stamps from faraway places that family and friends had given her since she was 6 years old.

But the Cultural Revolution saw collecting stamps as “bourgeois” - something only well-off middle-class people did, and therefore forbidden in a society that used violence to remake itself so that people dressed alike, spoke alike, and thought alike. The Red Guards hauled away much of the family’s things in bags. Ji-Li never saw her stamp album again.

“Home,” thought Ji-Li. “Wasn’t a home a private place? A place where the family could feel secure?”

Then Ji-Li’s father was detained and interrogated. The authorities asked Ji-Li to betray her family. She refused. When the terrors of the Cultural Revolution ended, she and her family were able to leave for a new life in the San Francisco Bay Area, where she still lives. Ji-Li Jiang is now a writer and teacher. Her book, Red Scarf Girl, is her attempt to, she writes, “Do something for the little girl I had been, and for all the children who lost their childhoods as I did.”

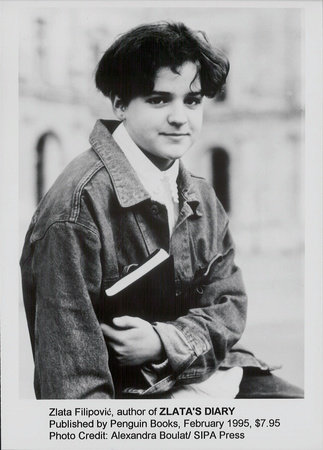

Zlata Filipović, b. 1980

When war came to her hometown of Sarajevo, in the Eastern European nation of Bosnia, Zlata Filipović was 11 years old. Until then, she did what every other young girl her age did: go to school, play, read, watch TV and movies, enjoy pizza and spaghetti, hang out with friends. She was getting more confident about her piano lessons, too. And, like other young girls, she wrote about her life in her diary, naming it “Dear Mimmy,” and entrusting it with her innermost thoughts.

“I was a happy-go-lucky girl who thought war was something that happened to someone else,” Zlata would later say, looking back as an adult.

“The kids,” as Zlata would later describe the adult politicians in charge of that part of the world, had other ideas in store. The Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia was breaking up, as Bosnia Herzegovina and others among the smaller republics that made up the country sought independence.

During this time of uncertainty, some politicians deliberately inflamed nationalist tensions between the many ethnic groups in multicultural - and previously largely peaceful - Bosnia. They tried to provoke mutual resentment among Bosnian Serb Orthodox Christians, the largely Catholic Bosnian Croats, Muslims, and Jews. Creating chaos for everyday people could be a powerful tool for those who sought to increase power and territory.

After Bosnia declared independence in March 1992, Bosnian Serb paramilitary fighters, assisted by the Yugoslav army, attacked the capital city, Sarajevo. On April 18, Zlata wrote in her diary, “War has suddenly entered our town, our homes, our thoughts, our lives. It’s terrible.”

She was no longer able to go to school because it was too dangerous. Her family, like most others who remained in the city, suffered lengthy electrical blackouts, lack of safe running water, no heat in winter, dwindling food supplies, and the constant stress and fear that they would be killed by gunfire from one of the 13,000 troops surrounding the city if they went into the streets.

People were desperate for clean water. Zlata’s parents and many others would go to the city’s fountains with buckets to bring water home, never knowing if they would be shot before they got back. In one particularly horrible incident, dozens of people were killed while they simply waited in line for bread at what had been Sarajevo’s beautiful central market.

Serbian and Bosnian Serb leaders wanted to make Bosnia part of a “Greater Serbia.” Their horrifying practice of “ethnic cleansing” involved trying to subjugate, drive out, or kill everyone who did not fit their ideas of what this Greater Serbia should look like. They and sometimes other groups in the conflict committed vicious atrocities against civilians.

Historians note that the siege of Sarajevo, which lasted from 1992 to 1995, was one of the worst in European history, claiming more than 10,000 lives, according to the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia. Experts believe that about 100,000 people total were killed in the Bosnian Civil War during those three years. These included more than 7,000 Muslim men and boys massacred in the town of Srebrenica, the worst act of genocide on European soil since the Holocaust.

Before the war, Sarajevo had been a beautiful, sophisticated city, filled with parks, trees, markets, mosques, synagogues, and both Orthodox and Catholic churches. During the war, Zlata wrote in her diary about how she felt seeing first the new post office near her home destroyed, then the Olympic stadium that had been built for Sarajevo’s hosting of the 1984 Winter Games. Her heart broke when children her own age, whom she knew well, were shot and killed.

Even during the war, Zlata continued studying her music and her school subjects as best she could. While the war continued, foreign journalists found out that a young girl in Sarajevo was keeping a diary, and they came to interview her. In 1993, her diary was published and she and her family managed to escape to Paris.

Today, Zlata is in her 30s. She is an Emmy Award-winning documentary filmmaker in Dublin, Ireland. Zlata’s Diary: A Child’s Life in Sarajevo was published in English in 1994. Zlata’s diary has been compared to that of Anne Frank, in that both girls witnessed senseless and horrific human suffering, but both held onto their hard-won dignity and their dreams of a better world.

Malala Yousafzai, b. 1997

As a toddler, Malala went with her father to the school where he worked. In the empty classroom, she would stand at the front of the room and “lecture” in baby talk. Later, as a girl, she would practice giving speeches in front of a mirror. It seems Malala was born to speak out, and that is exactly what she did.

Boys are more likely to receive an education in Pakistan than girls. However, Malala’s father was an advocate for girls’ education and ran his own school. He was the principal, teacher, and janitor! Malala and her schoolmates enjoyed school and were grateful for the opportunity to get an education. However, in neighboring Afghanistan, the Taliban were re-making the country to reflect a very extreme philosophy. In their minds, the West was bad, and any activities that seemed “Western” had to stop. This included listening to music, dancing, educating girls, and allowing women to venture out freely.

Malala was not going to let the Taliban stop her. She and her friends continued to attend school, and her father continued to teach them. Although they received threats, and even had to stop going to school when the Taliban were present in their area, they kept the school open, and the girls kept coming.

Malala was not alone. People all over the world were watching and growing concerned as the Taliban spread their ideology. As an outspoken and articulate girl, Malala frequently spoke to reporters about the situation for girls in Pakistan. A reporter from the BBC asked Malala to keep a diary of her experiences, and through this diary, people all over the world followed Malala’s advocacy for girls’ education.

This international exposure must have angered the Taliban. They sent men to threaten Malala and her father. Malala remembers looking online and seeing the death threat against her and simply closing the computer screen and making a decision to never look at those words again. As she put it, she would now “get back to doing what I was meant to do.” Defying the Taliban in her valley, she continued to travel to school.

The school day in October 2012 started out as any other day. Now fifteen years old, Malala rushed out the door in the morning to go to school. The biggest concern on her mind was an exam she had to take that day. Coming home after school, Malala squeezed in to the dyna (open-backed van) along with her schoolmates. They chatted as usual until the dyna came to a halt. Although she doesn’t remember it, a man came into the back of the van and shouted, “Who is Malala?” He fired three shots, and then everything went dark.

Malala woke up more than a week later in a hospital in Birmingham. During this time she had been in a coma, had been transported out of Pakistan to England for treatment, and the whole world had heard about her ordeal. The hospital in Birmingham received 8,000 cards for Malala, from well-wishers around the world. She was finally able to leave the hospital after several months, and had to recover in a new city.

In July, 2013, less than one year after being shot, Malala was invited to speak at the United Nations in New York City. In her speech, she said, “I speak not for myself, but for all girls and boys. I raise up my voice not so that I can shout, but so that those without a voice can be heard. Those who have fought for their rights: Their right to live in peace. Their right to be treated with dignity. Their right to equality of opportunity. Their right to be educated.”

In October, 2014, two years after being shot by the Taliban, Malala received the Nobel Peace Prize. She is the youngest person to have ever won this award. Today, Malala attends Oxford University and her work continues with Malala Fund. She is still working to ensure that girls can receive an education.